Digging ancestor mounds is sensitive work. Our spiritual leaders instructed us to use “tumuth”, ground red ochre mixed with cream or grease. It is used to help the spirits of our ancestors see the living and avoid direct contact, something that can be harmful. We put tumuth on our temples, wrists, and chest to protect us. We were also careful to “be of good mind” while we worked. We made sure to complete work before sunset because we shouldn’t be on spiritual sites after dark.

At the beginning and close of each field season, Stό:lō Elders and spiritual workers Vincent Stogan and Kenny Moses led ceremonies called “burnings”. These ceremonies honour and “feed” the ancestors who once lived at Qithyil by providing a feast for them. Both of these Elders told us that the ancestors were happy about the work being done and about the burnings at the site.

We worked together to understand the remains we unearthed at Qithyil. The archaeologists taught us a lot about what our ancient belongings had to tell. We taught the archaeologists our knowledge of Sq’éwlets history, our sqwélqwel, handed down from our grandmothers and grandfathers. The time flew by and we have now been working together for many decades, in an open way, teaching and learning. We have become great friends.

Taking Care Of Our Ancestors

As Stó:lō, it is very important that we take care of our families. We take care of both our living and our dead relations. We take care of our living relations with honour, respect, sharing, and giving. We honour our dead and our ancestors the same way. We respect them by carefully preparing and honouring their final resting places. We remember and share with them through ceremonies.

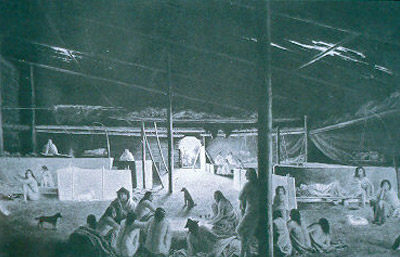

The ancestral site of Qithyil, and its surrounding landscape, is a spiritual place. Many of our old people are resting there. About 1,500 years ago, Sq’éwlets people began to use parts of their village as a cemetery. They moved somewhere else to live. As a way to honour their relations who had passed to the spirit world, they built huge earthen mounds like pyramids and big piles of boulders called cairns over their resting places. By 1,000 years ago, around the year 1000 in the calendar we use today, the building of ancestor mounds and cairns stopped at Qithyil. Our ancestors continued to build smaller ancestor mounds and cairns in the wider area.

Taking Care of Ancestors: Fieldwork Protocols

View Transcript[Betty Charlie]: They had to have good feelings when they went over there, and the way they went over there was the way they had to come back. Not bringing bad thoughts back from the mountains. Yeah, it’s all about respect.

[Dave Schaepe]: In 1992, and following particularly with regard to the work that was done focusing on the burial mound sites, and the burial mound features, that’s when protocol emerged, again as I understand it,and the use of témélh - the red ochre - as one of the significant parts of cultural protocols that have continued to be used to this day, particularly with field work involving excavations on sites. We as archaeologists are disturbers. We do disturbance, we create disturbance to sites. We disturb them. We take things away. We take things that don’t belong to us, from the Stó:lō perspective. That’s part of what we do. What we do in that happening can be justified in particular instances where there’s questions to be answered, that archaeologists can address; only archaeologists, in some cases, can really address those particular questions, given our work in the earth with objects. In order to counteract the disturbance, in order to not interfere or avoid harmful interactions with the community at large, and that’s the spiritual realm of ancestral community who, from a Stó:lō perspective, still is there, is still in these places, still inhabits the old village sites, are still connected to their things - the things that belong to them; their objects, their creations.

[Albert (Sonny) McHalsie]: When you leave too, call your name. So when we leave our cemeteries, we always call ourselves so we don’t leave. ‘Cause when you go to a cemetery, and you’re grieving for your loved ones, sometimes you can leave some of your spirit there. So that’s why we brush - so when we brush, we’re brushing anything bad, something that might have just latched on to you, so we’re brushing it off. But also when you call yourself, it’s making sure that you yourself don’t leave something there. So when you’re leaving just go, “Let’s go, Doug” - just say it in your head. “Come on Doug, let’s go.”

[Michael Blake]: Well, one of the protocols that became very important right at the beginning was that, because we were on a cemetery site, there was some potential for spiritual danger to all of the people who were working on the site. And, in order to protect all of the participants in the project, we were taught how to use témélh - red ochre, or Hematite, that’s turned into a red paint that we could use to mark our foreheads, and our chest, and our wrists, so that we would become visible to the spirits at the site.

[Betty Charlie]: It was for our protection, mostly for the people that are buried on this site. So, they’d see the témélh, and they’d know you were coming. And, so they could identify you, and it was also so while you were there, if you happened to pick up something like an old artifact that, something off of the artifact wasn’t going to jump on you. And then you’d have to take that back. It was for protection.

[Vi Pennier]: What I know of témélh is that it’s strong medicine. It’s a protector. It’s a healer.

[Lucille Hall]: I was just told that, it was to protect you, from spirits, and I was told that the spirits on the other side recognize you if you’re wearing the témélh. Otherwise, if you’re not wearing it, they can’t see you; they don’t know who you are. But once it’s in place, it doesn’t matter who you are; they know who you are. They recognize you. So it’s very important to wear it. Doesn’t matter who you are. You know - they recognize you. And that’s nice. You know, that’s something to be said about the spirits. So témélh is just - I’m very proud to wear it when I can. You want to be recognized. You want them to see you, even if it’s just for a brief moment. Yeah.

[Dave Schaepe]: In large part, with the ancestral community, the practice of burnings, spiritual burnings, offering, feeding the ancestors; these are practices that go back likely thousands of years, in that we’re seeing, in the work we’re doing in archaeology, we think particularly in relationship to the burial mounds, one way in which we see practices like this occurring in the past that continue to be used today in the community, and now are incorporated into our archaeological work. This project is overall about increasing the visibility of the relationships between you know, what’s otherwise an “us” and “them” kind of relationship, to be able to work together without harm coming to either of the parties, any of the parties.

So archaeologists applying témélh before they go on site, being instructed by the elders and by cultural workers, how to approach our work with a good mind. To be of good mind, to be of good heart, to leave your negativity behind. To do our work on site in the best possible way and to avoid conflict on site.

[Michael Blake]: Um, one of the conferences that took place was with elder Frank Malloway. And he and other elders, along with other community members at Sq'éwlets thought that it was really worthwhile excavating the mounds to the point where we could demonstrate that they were part of the Sq'éwlets cemetery. And that they were burial mounds, and not just constructions of earth. So then we did that. We proceeded to go ahead and excavate the centres of the mounds, following the instructions of the elders, and following the protocol that they developed for how we would go about doing it, and how the whole process should unfold. That was a really, really useful experience because we couldn’t have, we wouldn’t have known how to proceed within the community protocols without that kind of support from and advice and guidance from the elders in the community. It was absolutely essential to every part of the decisions about how we went ahead with what we did.

Download:

SD (40 MB) | HD (129 MB)

No archaeologist in this region had ever seen so many ancestor mounds in a big forested area. After talks with the Sq’éwlets chief-and-council, archaeologists excavated parts of several mounds. This included the largest, Ancestor Mound 1, at the south end of Qithyil. Each mound has carefully lined up boulders and cobbles, burned foods to ‘feed the dead’, and the resting bones of the ancestor. Many of our ancestors were put to rest with beads and tools made of stone. After learning what was inside a few of the mounds, archaeologists and Sq’éwlets cultural advisors returned everything to the way it was before the excavations and stopped digging. Our ancestors continue to rest at Qithyil, undisturbed and respected.